Hawaiian hurricanes maintain distinct identities which emerge from their naming conventions and travel patterns. The Hawaiian language serves as a treasured source for naming things throughout the islands.

The Central Pacific storms receive names that originate from Hawaiian language because this practice honors the profound cultural heritage of the islands. The intention behind these names demonstrates beauty yet their historical background shows complexity and occasional issues.

When Names Hit Too Close to Home

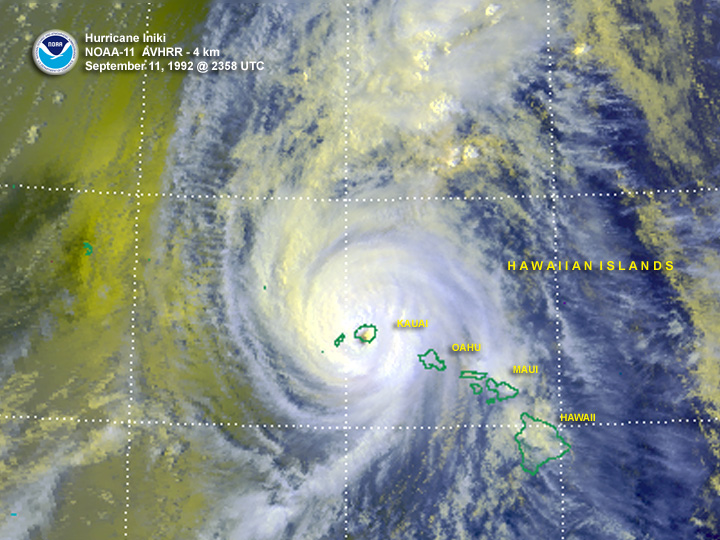

Let’s examine Hurricane Iwa from 1982 together with Hurricane Iniki from 1992. The storms created profound cultural impacts while leaving emotional wounds that remain with people today. The names of these storms represent severe physical and emotional impacts because “Iwa” means “thief” while “Iniki” means “to nip or pierce.”

- Hurricane Iwa struck just before Thanksgiving in 1982. It was “only” a Category 1 storm, but it caused around $250 million in damage, mostly on Kauai.

- Hurricane Iniki, a Category 4 beast, slammed into Kauai again in 1992, causing over $3 billion in damage and claiming six lives.

It was almost as if the names foretold their destruction. And that left many in the community questioning whether we were unintentionally assigning omens to our weather systems.

Changing the Narrative

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration responded to feedback by taking an uncommon step about Hawaii Hurricanes: they listened.

Together with Native Hawaiian language specialists NOAA made comprehensive changes to the Central Pacific storm naming list. The goal? Preserve cultural accuracy while removing storm names that might have negative or destructive meanings.

The current naming list includes names such as Akoni (“Anthony”) and Hekili (“thunder”) which have been selected with care to honor Hawaiian language traditions while avoiding names that evoke fear or trauma. This approach proves to be intelligent and mindful by demonstrating the strength of language when it is used deliberately.

Why Names Matter

Yes, naming Hawaii Hurricanes helps with public safety. It makes them easier to track, talk about, and prepare for. But in Hawaii, these names also carry emotional and cultural weight. That’s why the shift in how names are chosen matters so much.

It’s not just about avoiding bad vibes. It’s about showing respect for the language, the people, and the place. It’s about making sure we don’t unintentionally turn beautiful words into triggers.

Who’s in Charge?

Hurricane Center CPHC located in Honolulu monitors and gives names to storms in the Central Pacific Basin. The Central Pacific Basin encompasses the ocean area stretching from 140°W longitude to the International Date Line. The central Pacific experiences fewer storms than the Atlantic but the few that develop or move in here display remarkable intensity and lasting impressions.

And here’s the thing: Storms named after Hawaiian words are uncommon yet they produce significant effects that endure in both physical and historical contexts for Hawaii Hurricanes.

- Dora (2023) – Also crossed into Central Pacific; notable for contributing to record-breaking high surf

- Calvin (2023) – Entered Central Pacific after forming in Eastern Pacific; downgraded near Hawaii

- Hina (2022) – Named after the Hawaiian goddess associated with the moon; short-lived

- Hone (2021) – Minimal tropical storm far from land

- Walaka (2018) – Reached Category 5; threatened Johnston Atoll

- Ulika (2016) – A less intense storm that remained mostly at sea

- Oho (2015) – “To shout” or “cry out”; moved northeast away from the islands

- Neki (2009) – Means “Strong”; formed south of Hawaii and skirted the islands

- Aka (2006) – Short-lived but significant as part of a rare twin-cyclone event

- Loke (2006) – Means “Joy”; one of the strongest hurricanes ever recorded in the Central Pacific

- Paka (1997) – “Clear” or “fair weather” (ironically caused extensive damage in Guam)

This isn’t just about hurricanes. It’s about identity. It’s about how we, as a community, choose to represent ourselves—even in the face of chaos.

By bringing in Hawaiian language scholars and rethinking the way we name our storms, NOAA didn’t just correct a list—they acknowledged a culture. They showed that even in government systems, there’s room for respect, collaboration, and growth.

So the next time you hear a Hawaiian-named storm approaching, know this: it’s not just another blip on the weather radar. It’s a name chosen with purpose—rooted in language, shaped by history, and hopefully, free from fear.